The Good Samaritan: on the care of persons in the critical and terminal phases of life

- This post is also available in: Nederlands

- This post is also available in: Français

Bro. René Stockman, Superior General of the Brothers of Charity

On 22 September last, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith presented and published an important document on how, as Catholics, we should care for people who are in the critical and/or terminal stages of life. At the heart of the document lies the affirmation that respect for life is always absolute and that no act that goes against it is admissible. It confirms and validates the vision and doctrine of Pope Saint John Paul II in his encyclical Evangelium Vitae and updates it so to speak. After all, quite a bit has happened in the past 25 years and in some areas, it is not just an evolution but rather a revolution. Just think of the advances in medical science, which succeeds in combating life-threatening diseases better with new techniques, as a result of which people live longer but sometimes also experience a longer and more severe terminal stage of their illness. Moreover, we cannot turn a blind eye to the pernicious social evolution in which euthanasia has been established as a legal framework in many countries and is claimed by some as a right in the event of terminal and irremediable suffering, both at the somatic and mental level.

Therefore, it is only right that the document should start with an in-depth reflection on the essence of ‘proper care’ and the place of suffering in life, before going into more specific situations and the answers that can and must be given to such situations. I try to follow the broad outlines of the document and add a few personal considerations. After all, a document of this level is an invitation to encourage more personal reflection.

The Good Samaritan

An icon of proper care, the Good Samaritan serves as an example who spares no effort to surround the person he meets on his way with the best care because he sees the image of God in man. That is the basis of the human dignity that is found in every human being. The Samaritan looks at his neighbour with a “heart that sees”. It is the way he looks at the sick person: with a profound compassion, and from this compassion health care workers and all those who are close to the sick are invited to take up their task: from a basic attitude of love. This is also the heart that God has for every human being: a heart filled with love and compassion, and this is the divine love that we must convey to the sick. God’s universal and at the same time personal love for every human being must remain the orientation and the basis with which people treat each other, and especially the sick, including those who are terminally ill. It is about caring for every human life and for the life of each person in particular. This care will always be based on the golden rule: “Do unto others whatever you would have them do to you” (cf. Mt 7:12). This will manifest itself in health care in a twofold dimension: promoting human life and avoiding any form of harm. Hospitals should therefore always be places where the fragility of life is handled with great care. This fragility manifests itself particularly at the end of life, where therapy will turn into pure care for the person who is facing death. This must remain an integral part of health care, and this document focuses on this stage of life.

The suffering Christ as a sign of hope

Illness is always associated with suffering, and health care workers are therefore directly confronted with the suffering of those they treat and care for. Being open to this suffering, seeing how they can alleviate it and how they can be truly compassionate to those who suffer is part of their core task. Medical care can therefore never be reduced to a number of medical-technical actions, which require a high degree of technicity. Health care becomes fully professional only when all dimensions of the human being are taken into account, including, and above all, the human being who suffers and who questions this suffering: why, what for, how long… Pain and suffering can be reduced through medication, but only really alleviated by lending a sympathetic ear, a compassionate heart, a caregiver who is and remains a true neighbour for and with the sick person.

The existence of suffering remains a mystery of life that is difficult to understand. It is right to do everything, as already indicated, to prevent pain and suffering and to heal it. Progress within the medical world has already been able to alleviate a great deal of suffering. Nevertheless, suffering remains an essential part of life, of every life, and especially towards the end of life it can be very hard. On the face of it, the most obvious answer to the question of the place of suffering in life is that it is completely useless, and today we also see the consequence of this thinking: the ease with which euthanasia is proposed and opted for when suffering is experienced as being hopeless. Any question of a possible meaning within suffering is dismissed as a disgraceful aberration of religious thought. In this area, too, one is often accused of having an outdated view of humankind if one so much as dares to bring up the meaning of suffering at the sickbed.

Nevertheless, as Christians, we must have the courage to look up to the Cross on which Christ suffered, suffered for us, redeemed us with his suffering, and through his suffering also suffered with us.

Two elements are highlighted here in a special way. On the Cross, Jesus looks up to his Father from the belief that he will not forsake him and he looks down on his Mother and the disciple who is with her. At that very moment he asks his Mother to care for John, to care for every human being, and he asks John, and each of us, to look to Mary as our mother. The care for one another takes on a special meaning here: a care in silent presence at the foot of the Cross, to comfort one another and to continue to do so. But at the foot of the Cross, they also look upwards and so participate in the event of salvation that takes place precisely in the suffering and death of Jesus Christ on the Cross, and the perspective of the resurrection opens up for them as well. Staying with the suffering sick and caring for them on a human level and helping them on a spiritual level to turn their eyes to the Cross to see the hope of the resurrection through the cross of their suffering: these are the two movements that can happen here. We cannot impose this surrender of faith, but as Christians we must have the courage to offer it to fellow believers. Perhaps too much hesitation has arisen to put the crucifix in the hands of those who are badly suffering and dying, which used to be common practice. The text of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith therefore calls for this spiritual aspect not to be neglected in the case of terminal suffering, and especially in the case of palliative care, and for a certain degree of hesitation to be overcome.

There are many cultural obstacles today that obscure the absolute dignity of every human life

Today, however, the Good Samaritan encounters a number of obstacles in the fulfilment of his loving care and also in the way in which he tries to deal with suffering in a committed way that hinder both his loving care and his dealing with suffering. The document identifies four obstacles that are also real hindrances to our efforts to preserve and promote absolute respect for every human life, which is the true motivation for our loving care for all life and in all circumstances.

First and foremost, there is a very one-sided interpretation of the concept of ‘quality of life’, whereby any form of serious suffering is considered a threat to human well-being. It is as if only physical well-being constitutes the totality of human well-being and other dimensions do not matter. There is no longer any distinction between the so-called accidental quality of life and its essential quality, with which we consider life as such. Even when the accidental quality of life is very low, the essential quality of life can still be very intact. We often experience this with elderly people who have to go through life with many limitations, limitations that only increase, however they do not lose their joy of life and continue to find real meaning in life.

In addition, the concept of compassion has been redefined, and today it is considered to be a work of mercy to release a person from great suffering through euthanasia.

The third element is a growing individualism, in which a person demands absolute self-determination, autonomy, and freedom and no longer wishes to take into account their responsibility towards others and the impact that their actions can have on others. It becomes an ‘every man for himself’ mentality.

Finally, reference is made to the words of Pope John Paul II, who spoke 25 years ago of the danger of evolving into a ‘culture of death’, and to the speeches and texts of Pope Francis, who has on several occasions criticized the throw-away culture in which we find ourselves today.

After this thorough reflection on what we might call ‘proper care’, we arrive at the document’s phrasing of a number of issues that we face today within this health service, some of which are difficult to reconcile with this ‘proper care’. This is why the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith considered it necessary to draw up a number of clear guidelines and these should therefore be regarded as doctrinal statements of the Magisterium. First, the general view on the performance of euthanasia and assisted suicide is discussed, after which a number of more specific situations are explained.

The teaching of the Magisterium concerning euthanasia and assisted suicide

The vision is formulated very directly and clearly: euthanasia and assisted suicide are always intrinsically evil acts, regardless of the situation. Why? Because life as such has absolute value and deserves absolute respect. This doctrine is based on the natural law, on the written Word of God, and repeated throughout the Catholic Tradition by the Magisterium. It follows that any formal or immediate material cooperation in such an act is a grave sin against human life. The value of life, the autonomy of the patient, and the care relationship between patient and caregiver can never be placed on the same line and simply weighed up against each other. The value of life is absolute and takes precedence over all other values.

Health care workers and those who organize this health care must always put themselves at the service of life and support it to its natural end and cannot engage in any practice of euthanasia. And no health care worker can be obliged to do so. Therefore, euthanasia and assisted suicide are a moral defeat for those who build a supportive ethical reflection around these practices, who perform euthanasia, and who help carry it out.

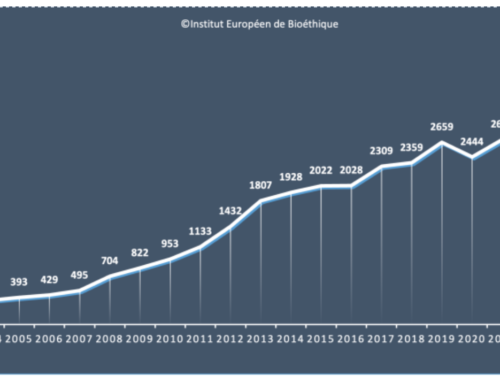

Where euthanasia is made legal, this is a sign of a degeneration of the legal system. The document deplores the fact that, as a result of the implementation of this legal provision, many people have already died by euthanasia, many of them because of mental suffering and depression. The request for death in these cases is often a symptom of the illness aggravated by feelings of abandonment and hopelessness. It is precisely to this that extra attention must be paid.

A number of specific concerns and practices

- Radically rejecting euthanasia does not mean surrendering to therapeutic obstinacy. It is therefore allowed to discontinue certain therapeutic actions when it is established that they can no longer be of any added value to the sick person and can even cause more harm than relief. However, the cessation of therapeutic actions must never have the aim of accelerating death. The principle of proportionality applies here, in which the general well-being of the patient and absolute respect for life must always be paramount.

- As far as the terminally ill are concerned, the essential physiological functions, particularly in terms of nutrition and hydration, which may be administered by infusion, will always be maintained. For this reason, allowing a person to die by no longer administering fluids is never permitted.

- A great deal of importance is attached to palliative care. This care must not be limited to the somatic, but must also respond to affective and spiritual needs, without neglecting the support of the family. These are the moments when genuine solidarity and love can be experienced, which can profoundly reverse the hopelessness of the situation. This is why palliative initiatives are very important, where people can receive professional care at a terminal stage in their lives and where the family can also receive the necessary support. However, there are serious objections to the trend of linking palliative care to the possibility of euthanasia or assisted suicide.

- On the other side of life is the care of prenatal life and paediatric medicine. Here, it is clearly reiterated that life must be respected right from conception and that children already suffering from illness in their mother’s womb or diagnosed with malformations must also be treated and cared for appropriately. It is, of course, with great concern that reference is made to the growing trend towards prenatal diagnosis to determine whether the expected child is normal, and, if an abnormality is detected, such as Down’s syndrome, the only alternative is immediately to propose an abortion to the parents. This is moving towards a dangerous development of a eugenic mentality.

- If the pain becomes unbearable in terminal suffering, sedation is advised, and therefore permitted, up to and including deep palliative sedation, but always with the patient’s consent if the patient is competent to do so. However, the use of palliative sedation as a concealed way to perform intentional euthanasia is prohibited.

- For people living with a very low level of consciousness or even in a so-called vegetative state, it is necessary to continue care and provide them with sufficient physiological support, i.e. sufficient fluids and nourishment, possibly by artificial means. Only treatments that are completely useless or even more harmful than beneficial can be omitted.

Conscientious action as health care workers within Catholic health care institutions

Where euthanasia and/or assisted suicide is legally possible and considered as an alternative medical practice, health care workers within Catholic health care institutions cannot under any circumstances participate in these practices, on the principle that one should obey God rather than men (Acts 5:29). It is therefore never morally lawful to participate in an act of euthanasia or to consent to it by word, deed or by abstaining from a clear position on the matter. As a general principle it is stated that: “Christians, like all people of good will, are called, with a grave obligation of conscience, not to lend their formal collaboration to those practices which, although allowed by civil legislation, are in contrast with the Law of God. In fact, from the moral point of view, it is never licit to formally cooperate in evil.”

Governments must acknowledge the right to conscientious objection and health care workers have the right to claim it.

Health care institutions must resist the sometimes strong economic pressures placed on them to allow euthanasia. Instead, they will give a strong testimony by speaking out clearly and publicly on the subject and by unconditionally and formally aligning themselves with the teachings of the Church in this regard. If they fail to do so, they must realize that they are placing themselves outside the teachings of the Church and may therefore lose their Catholic identity.

Institutional collaboration with other facilities to be able to refer patients requesting euthanasia in this way is also morally unacceptable.

Pastoral accompaniment and administering the sacraments

The Church is called to spiritually accompany the faithful and offer them the healing resources of prayer and the sacraments. This accompaniment always involves the exercise of the Christian virtues of empathy, compassion, and consolation. Administering the sacraments must therefore always be seen as a culmination of this pastoral accompaniment and care.

The Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation requires the penitent to show contrition for the past and to resolve to sin no more. However, if the penitent is resolved to request euthanasia or assisted suicide and to have it performed, they cannot receive the Sacrament of Penance. Only if they renounce it in confession can sacramental absolution be given to them.

This does not mean that pastoral care ends there. Not accepting the act does not mean abandoning the person. One will remain close to this person and still hope that they will be able to experience conversion.

However, it is not permitted for those who administer pastoral care to be physically present during the performance of euthanasia or assisted suicide. This could give the completely wrong impression that the Church approves of this act.

Conclusion

We would like to invite everyone to read the document in its entirety and also to discuss it. The first part gives us a clear framework in which we should place proper care and its importance. For those who are active in the field of health care and help to organize it, it remains a challenge to always focus on this ideal, following in the footsteps of the Good Samaritan as our icon to imitate. The guidance given here on how to deal with suffering is only a stepping stone and an urgent invitation for further reflection if we really want to continue to nurture our care on a Christian basis. Let us dare to make this reflection, also as a group. Ultimately, the specific guidelines we receive in this document are clear and at the same time demanding, but necessarily enlightening at a time when there is a great deal of confusion and where social trends really run counter to the deepest Christian values and the ultimate value: absolute respect for all life. Above all, let us hope and pray that this document may help us and many others to bring this necessary clarity to this very sensitive issue and, at the same time, that it may be a confirmation for all those who continue to work to defend life from the moment of conception to the moment of natural death. We also pray for those who make a tangible commitment through very personal care and attention to the promotion, support, and healing of every neighbour whom we always consider to be a child of God.

Bro. René Stockman

Superior General

Brothers of Charity