Biography:

Anne Lastman.

Constantine’s contribution to Christianity was his issuing of the edict of Milan 313 which granted religious tolerance throughout the Roman Empire, ending persecution of Christians convening the Council of Nicaea (325) to establish Christian doctrines by theologians of the time most specifically the three Cappadocians who were Byzantine priests, monks who defended appending to Christianity false doctrines.

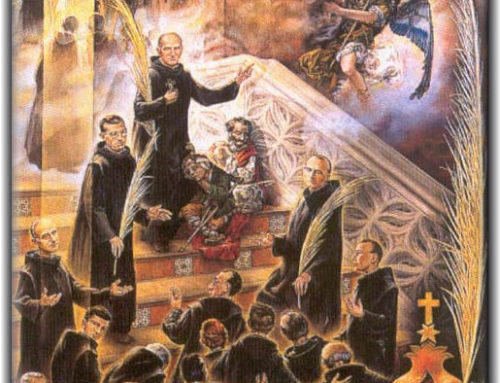

Gregory of Nyssa, one of the trio known as the Cappadocian Fathers, is perhaps the best known of the three. Together with Basil the Great (Gregory’s brother) and Gregory of Nazianzen, his friend, formed a formidable group of fourth century defenders of the faith.

The family of Gregory and Basil were Christians and belonged to the upper class of Cappadocians. Indeed, they were considered to be of the elite and wealthy.

Gregory was born in Caesarea c AD 335 into a family of distinction. His father, Basil, was a rhetorician and his mother (Emmelia) was the daughter of a martyr. Gregory was a member of a large family of ten children. His father appears to have died very early in Gregory’s life and the care for the family fell to his grandmother Macrina and the mother Emmelia.

The family of Gregory was made up of five boys and five girls, most of which only minor information is recorded. However, it’s known that Basil (named after his father) one of the elder brothers, and Macrina his sister (an ascetic, named after grandmother) were very influential in his life. It appears that Basil was responsible for the secular education of the young Gregory whilst Macrina was responsible for his religious education, but he also calls Basil his teacher in his hexaemeron and the De Opificio Hominis. Gregory gives credit for any of his own acclaimed works to his brother Basil, and any work which he considers inferior, he claims as his own. This perhaps suggests an awe of his brother or perhaps a deep sense of humility.

Gregory appears to have been a shy and retiring individual who, unlike his brother Basil and his peers, did not have the benefit of education at centres of learning such as Athens, Constantinople or other foreign places. Whilst his studies were comprehensive, he does not appear to have studied towards a profession and supported himself from family inheritance.

There is a suggestion that Gregory was married to his friend’s (Gregory of Nazianzen) sister, Theosebeia, before he was made Bishop of Nyssa. The idea that Gregory may have been married to Theosebeia is found in a letter written by Gregory Nazianzen who seems to be consoling his friend Gregory, “Theosebeia, the fairest, the most lustrous, even amidst such beauty of the Episkopi, Theosebeia, the true priestess, the yokefellow and the equal of a priest.”

Gregory’s ultimate conversion to the Christian faith was due to Macrina’s(sister)influence in this area. Her strong influence helped to change his existing way of life and lead to a withdrawal from secular activities and to withdraw to his brother’s (Basil) monastery in Pontus where he devoted himself to study of scripture and the works of Origen. One of his more famous treatises On Virginity is believed to have been written during his stay at the monastery. Indeed, this relationship with his brother Basil appears to have strengthened further after his retreat to the monastery.

In AD 365 Basil was summoned by Eusebius of Caesarea to assist him with the ongoing difficulties posed by the Arian controversy. To support his own position against the heresy and the Arian defenders, Basil surrounded himself with known and trusted defenders of the orthodox position. To this end he enlisted the help of Gregory (by consecrating him bishop) to undertake the bishopric of Nyssa a small and relatively unknown see near of Cappadocia, and Gregory of Nazianzen to the see of Sasima though he left this see without having achieved much due to poor conditions and jurisdictional issues.

Life for Gregory in his See of Nyssa appears to have been very difficult. It has been suggested that he was not suited for the role of bishop. Indeed, his life is believed to have been more of enduring and his inexperience and misjudgements, due to the inexperience, often led to the necessity for intervention by his more astute and learned brother, Basil. A charge of embezzlement is reputed to have been brought against him; however, this was eventually dismissed.

Owing to supposed charges by the pro Arian Demosthenes he was eventually deposed of his bishopric (AD 376). Gregory’s refusal to attend to and answer to the charges made against him led to his deposition from his see which was followed by exile in AD 376, and retirement for a time in Seleucia. Even here his difficulties persisted. However, following the death of Emperor Valens in AD 378, the last patron of Arius and Arianism, Gregory was restored to his see of Nyssa.

Following the death of his brother Basil at the young age of 50 years and the death of his beloved sister Macrina, Gregory took over a greater range of responsibilities than he had previously. He stepped into the place vacated by the death of his brother Basil and became a strong defender of the faith in Nicaea . His reputation by this time was so illustrious that his authority was not questioned. As a senior prelate at the synod of Antioch in 341AD he was chosen to reform the Church in Arabia which had allowed corruption to become entrenched there. Address other theological issues and defining Trinitarian belief.

Gregory’s reputation was enhanced further, by the call of Theodosius in AD 381, to be one of the 150 Eastern Bishops to attend the council at Constantinople. Here he championed the Nicaean cause and defended the Nicene Creed. Shortly before the close of this council Gregory was nominated as one of the Bishops who were to be regarded as the central authority of the Catholic communion. Little is known of his later years, and the last record is of him attending the Synod Constantinople in 394 AD. In reputation he was equal to the highest. His name at the Synod of Constantinople appeared with the most respected, the metropolitans of Caesarea, Iconium, Constantinople and others. These bishops were singled out because of their orthodoxy and because of their defense of orthodoxy.

Gregory died in 395 and the Greek Church commemorates his death on January 10 and the Latin Church commemorates his death on March 9.

HIS WRITINGS.

Gregory’s monumental work Against Eunomius is a defense of the Nicene Creed This work was begun by Basil (his brother) which he continued after his brother’s death. This work consisted of 12 books although in its original form it was in 3 books. He also pursued the defense of the role of the Holy Spirit. His Great Catechetical Discourse is a defense of the Christian faith against Jews and pagans. On Virginity is a treatise more on nobility, purity and virginity of the soul than physical virginity. Where other writers wrote on physical virginity, Gregory appears to be calling for the greater virginity, that is, purity, incorruptibility. Ten Syllogisms was directed against Appolinarists, who were allied to Manichaeans and whose teaching was that Jesus was only half God and half man whereas the Christian faith teaches that Jesus was fully God and fully man.

Apollinaris particularly insisted that the Logos had replaced the human mind or soul in the Christ. Dialogue on the Soul and the Resurrection was written AD 379 after his return from the Synod in Antioch and found his sister near death. This dialogue between Gregory and Macrina is supposed to be the thoughts of Macrina on the last things, that is, the nature of the soul, immortality, death and end of life issues . The De Instituto Christiano and his Hexaemeron inspired the Opificio Hominis – on the origins of man – although there has been some dispute as to the authorship of these.

The bulk of Gregory’s work consists of anti heretical, dogmatic, exegetical and ascetical treatises. However, he also left behind “a number of homilies and orations, sermons for feast days, some moral and dogmatic homilies, panegyrics on saints and three funeral orations”. Indeed his writings appear to clearly testify to his reputation as an orator. His Oratio Catechetica Magna is his superb attempt at writing a complete account of Christian theology and is intended for those who teach the faith and for those seeking conversion.

Further to this, Gregory’s mystical works include homilies on the psalms, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, and eight homilies on the Beatitudes. His work on the Sacraments of Baptism and the Eucharist are also of renown.

The work of Gregory (and the other Cappadocian Fathers) on The Trinity affirmed ‘identical in essence,’ (homoousios) and at the Council of Constantinople (381) the issue, which convened the Council of Nicaea in 325AD, was brought to a completion. Arius’ theory that Jesus was not of the same “ousios” or “essence” as the Father was put to rest. Further, there was a reassertion of the Nicaean formulae by developing a theology of Trinitarian life of God. It was at this council that the Trinity, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, were declared one God, one substance, three persons each having a uniqueness of being and each is distinguished by His own attributes. Both Councils Nicaea (AD 325) and Constantinople (AD 381) were concerned with the doctrine of the trinity with the former leading to a definition of the role of the Son – logos, and the latter to a definition of the role of the Holy Spirit within Trinity. Indeed Trinitarian theology became, for Gregory of Nyssa, his noted area of work. His opus.

The Cappadocians, of which Gregory was one of the trio were formidable during a part of the fourth century which was most actively involved in the Arian controversy. The writings of these three Church fathers were prolific with each of them being remembered as having contributed much towards the search for a Christian doctrine of God. It was during these early times that the church was attempting to formulate doctrines for belief.

The renown enjoyed by the Cappadocian Fathers, Basil the Great, Gregory of Nazianzus, and Gregory of Nyssa is related to their defense orthodoxy of the faith and contributing to the suppression of Arian, neo-Arian and part Arian ideas. Further, these Fathers were involved in the development of Christian culture following the “legalization” (Constantine) of Christianity and it becoming the religion of the Roman empire (380AD). Each of these fathers is remembered for their writings and the influence they had in the defense of the faith. Gregory of Nyssa and Gregory of Nazianzus were especially instrumental in finally defeating the Arian controversy, and Basil is not only remembered for his own efforts in the Arian controversy but also for his efforts in the founding of monasteries and drafting of monastic rules which are still in use in the Eastern Churches.

Bibliography:

Chadwick, H., The Early Church (London: The Penguin Group, 1967)

Davis, L.D. (SJ) ., The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787) Their History and

Theology. (Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1990).

Ettlinger, G.H. (SJ)., Jesus, Christ & Saviour, Vol. 2. (Delaware: Michael Glazier, 1987).

Frend, W.H.C., The Rise of Christianity (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984)

Haslett, I. (ed.) Early Christianity. Origins and Evolution to AD 600 (London: SPCK, 1991)

Holmes, J.D. & Bickers, B.W., A Short History of the Catholic Church (Kent: Burns & Oates, 1987).

Jurgens, W.A., The Faith of the Early Fathers, vol. 2. (Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1979)

Schaff, P and H. Wage (Eds), Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Vol. 5. 2nd Series. Gregory of Nyssa:

Dogmatic Treatises, etc. (Massachusetts: Hendrickson, 1995)

Stevenson, J. (Ed), Creeds, Councils and Controversies (rev. ed. By W.H.C. Frend: London: SPCK, 1989).

Young, F.M., From Nicaea to Chalcedon (London: SCM, 1983).