Physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia – creating a resistance movement

Vincent Kemme

Rome, September 23rd, 2017

MATERCARE Conference

Ladies and gentlemen,

It is an honor for me to be able to speak to you during this 25th MaterCare Conference in Rome, where we reflect on the statement “Catholic Health Professionals Can Still Deliver”. Allow me to introduce myself (2): I am a biologist form the Netherlands, living in Belgium for 17 years now. I studied at Utrecht University, the city of cardinal Willem Eijk, who opened this conference, and had my career in secondary education both in the Netherlands and Belgium. I am what they call ‘a revert to the Catholic faith’, after being an agnostic for many years, though I came from a Catholic background. So I know what it is to have a non-religious perspective with regards to religion, faith, life issues and ethics. From my coming back to the Catholic faith (during my biology studies) onward, I specialized in the relationship between science and faith, as well as in bioethics in the broadest sense of the term: from sexual ethics, to beginning and end of life issues, to ‘human’ or ‘integral ecology’.

Almost ten years ago, after my career in education ended, I started ‘Biofides’, an apostolate on faith, science and ethics. It aims to clarify the ‘big questions’ on life, existence and morality to a larger public, from a reasoned Catholic perspective, open to dialogue with people of all walks of life, with religious or philosophical backgrounds. Amongst other activities, we discuss these questions on recurring radio shows, both in the Netherlands and in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, and talks in the Dutch, English and French-speaking world. In 2009, I was asked to join the Board of the bilingual Catholic Medical Association of Belgium. Since 2016, I am the editor in chief of its trilingual quarterly ‘Acta Medica Catholica’ (Dutch, French and English). In the meantime, I got involved in both the European and World Federation of Catholic Medical Associations (FEAMC and FIAMC) and was asked to join the newly created Bioethics Committee of FIAMC. And I consider it to be a great privilege to be able to contribute to the reflection in these bodies on the question “How Catholic health professionals can still deliver”, in a way that is faithful, reasonable and ethical. My wife and I are members of ‘Emmanuel’, the international lay community founded by Pierre Goursat and Martine Lafitte in Paris in the early seventies of the last century, and we are now responsible for the Flemish sector of this community. We are the happy parents of six children and, since Easter Sunday of this year, we became grandparents for the first time.

Euthanasia in the Low Countries

The theme that has been assigned to me is “Physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia – creating a resistance movement”. As I come from both the Netherlands and Belgium, the first countries in the world to legalize euthanasia, in 2001 and 2002 respectively, it might be helpful to offer some information on the practice of euthanasia in these – geographically – ‘low countries’ in Western Europe (3). First of all, in both countries, the numbers of reported (!) euthanasia cases have risen significantly: from 2000 to 6000 in the Netherlands and from more than 260 to more than 2000 in Belgium. In this talk, I will make no distinction between euthanasia and medically assisted suicides because the vast majority of medically assisted deaths in both countries are cases of euthanasia where the physician (or their nurse) administers death to the patient. So the distinction is not relevant for our reflection of today.

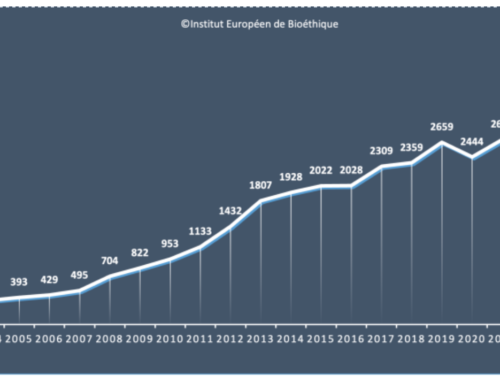

As you may know, Belgium is a country with a northern Dutch-speaking region called Flanders, a southern French-speaking region called Wallonia, and the French (and Arab!) speaking capital of Brussels, somewhere in the middle. This means that Flanders is culturally strongly oriented toward the north – the Netherlands, whereas the regions of Brussels and Wallonia are more oriented toward the south – France. This means that there are significant cultural differences between the two linguistic communities in Belgium, although there is also a lot of overlap, especially because of many ‘mixed’ families, political and economic exchange, the federal governmental structure, the royal family and the national soccer team. But the differences are clearly reflected in the number of euthanasia cases since the legalization in 2002: 80 % of the cases are to be found in Flanders, only 20 % in the French-speaking parts of the country! (4) Flanders, is strongly influences by the Netherlands, my native country that has the dubious honor of being the first country in the world to have legalized euthanasia, since World War II and the Nuremberg trials. As you can see in the slide on euthanasia in Holland – it is better to say ‘the Netherlands’ because ‘Holland’ is just one of these ‘Netherlands’ – in 2015, the graph of the number of euthanasia cases in the Netherlands seemed to level off somewhat (5), but optimistic reactions in the more liberal media where brutally corrected this year when it turned out that the total number of registered cases had exceeded the threshold of 6000 (6). And there are no signals that this rise in both countries is coming to an end very soon. This means that in Belgium, 2000 cases of euthanasia or medically assisted suicide are reported in 100,000 deaths in 2015 – in a country of about 11 million inhabitants – 80 % of which in Flanders; that is 2 % of all deaths. In the Netherlands, 6000 cases are reported in 150,000 deaths, which is 4 % – in a population of 17 million. (7) This means that the time has come, at least in the Netherlands, that euthanasia or medically assisted suicide is increasingly becoming a ‘normal’ way of ending one’s life, and this is perceived, or at least so it seems, as a sign of progress in a modern secular society, where we take life and death into our own hands, as we do in any other field of our existence.

If I were to describe the prevailing culture in today’s Dutch-speaking world, the Netherlands and Flanders, than I would use – in a somewhat provocative way – five ‘isms’ of which I admit that the number, the order as well as the choice are open to debate: welfarism, secularism, relativism, reductionism and pragmatism (8).

In this very rich part of the world – Antwerp, Rotterdam and Amsterdam are three of the biggest ports of Europe and the world – we cherish our welfare enormously and do not like hardship or suffering at all.

For this well-being, we do not need entities like churches, religious beliefs or any transcendent level of thought on religion and morality: those are subjective. The world as we perceive it is in our hands and it is up to us to make the best of it.

To the question of what is true and good for the human person and for humanity, nobody can claim to have the answer: everything is relative (apart from relativism: that is an absolute!).

So we reduce all existence, and human existence especially, to the tangible, temporal, special and measurable, the biological as far as (human) life is concerned. Other levels of thought, and morality even more so, is highly suspect.

We prefer pragmatic solutions for concrete problems, without many philosophical or ethical considerations. If suffering gets ‘unbearable’, euthanasia is a ‘perfect’ and completely ‘reasonable’ solution.

Of course, this description is somewhat caricatural and provocative, but it gives you an impression of the local mentality. And, of course, these tendencies are far from unique for the Dutch-speaking world.

A few years ago, the wife of a French Catholic hand surgeon asked me, not far from here in Rome, where all this liberal ‘crap’ – she used a similar French word – began in Holland. I gave her the following answer, not claiming that this is ‘science’ or ‘proven’ in any way, but she still refers to my answer every time I meet her. I said that if the devil wanted to destroy Christianity and Western civilization in Europe and elsewhere, the Netherlands, with its stubborn materialism and secularism, must have been the best place to creep in and corrupt that civilization from within, in order to have it spread throughout Europe and the rest of the world. Again, I have no scientific proof for this speculative theory, but there might be some truth to it. In any case, I believe that it is a spiritual problem, first and foremost, and that in the end it is the ‘fallen angel’ who is to blame, not the actors on the ground, who are oftentimes ignorant, ill-trained in the faith and in ethics. So I do not like ‘the blame game’, the constant repetition of what went wrong, pointing to ‘liberals’, ‘atheists’, ‘freemasons’, who have a ‘strategy’ – which in itself is not a sin – or even priests and bishops – the pope included – who could have been more outspoken or ‘orthodox’. To a certain extent, we all bear responsibility in allowing trends to take over and oftentimes reacting on it in an a way that may only do more harm – as we unfortunately have heard during this conference.

Of course, as my fellow Dutchman cardinal Eijk already explained to us in one of his two talks earlier this week, there is the slippery slope, once the door to euthanasia and assisted suicide is opened (9). Starting from the physical or somatic, we end up in the realm of the psychiatric, then we open up the door to euthanasia for children, and now, the debate is ongoing for the legalization for ‘those who feel that their life is complete’. So the question is: ‘who’s next?’ People with disabilities? Mentally unstable prisoners? Who knows…

Resistance

The question, however, that I was asked to talk about is ‘how to create a resistance movement’ against these developments (10). And I must say that coming from the culture where I live, the answer is not so simple. How do you ‘resist’ what you would call a ‘tsunami of secularism’ – or shall we say: ‘a hurricane of secularism’ – these days. Sometimes, we are confronted with phenomena that, at that moment, are stronger than us and that we have to accept are going on anyway, whether we like it or not. Some of your countries are in the process of legalizing euthanasia right now, but in the Netherlands and in Belgium, these are events from the past: euthanasia was legalized more than 15 years ago. And we were not able to ‘create a resistance movement’ that prevented it from happening. So what is there left to do, to ‘resist’ what pope John Paul II called ‘the culture of death’?

Faith

My answer to that question is threefold (11). In my view, our ‘resistance’ should be on three levels: the spiritual (or faith) level, the philosophical level of anthropology and ethics amongst others: the level of reason; and thirdly: the level of science and medicine, your practice. I must conclude from what happened in the Dutch-speaking world, that that is a direct link between the absence of God in our culture, through skepticism, and atheism, and the legalization of euthanasia. We live as if God, the first and final cause of life, does not exist and we become gods ourselves, judging the value of lives according to our own criteria, mastering life on our own terms. The answer to that problem is rediscovering God in our lives by opening up our hearts and minds and inviting others to do so. And the only way to be able to do so is by having a prayer life ourselves, being rooted, on a daily basis, in God, by taking time for Him. And to do so not by saying “Listen God, your servant is speaking to you,” but by saying: “Speak Lord, your servant is listing to you” (1 S 3:10). This is a conversion of our hearts and minds that is needed, starting with ourselves. If there is a ‘battle’ to win, in our secularized culture, I believe that it is first and foremost a spiritual battle that starts in our own hearts.

This conversion of ourselves in the first place, this being more rooted in God, will fill our hearts and minds with a love and wisdom that is needed to understand our contemporaries and love them, even if they oppose us and our views on human life. We are called, in Christianity, to love even our ‘enemies’. We will learn to distinguish, for instance, between the ‘sin’ and the ‘sinner’: the person before us on the one hand and his views and practices on the other. We will become that good Samaritan, as physicians and as citizens, that is there to help our neighbor rather than to judge him. And we become more willing and able to bear witness of ‘the hope that we have, with gentleness and respect’ for everyone that crosses our path (1 P 3:15).

In the Emmanuel Community that my wife and I belong to, we have three key words that describe our spirituality: adoration, compassion, and evangelization (12). First of all, we commit ourselves to spending a long time on prayer, if possible before the blessed sacrament, every single day, in order to have our hearts filled with God’s love and wisdom, with compassion for every single person that we come across, whatever his or her situation, stance or practices are, and to be ready and willing to share this love, goodness and wisdom of God with him or her, if possible, sometimes with words, more often in our deeds. Our community, 11,500 members now throughout the world, half of them in France, has lay members, consecrated brothers and sisters as well as priests. Among the lay members, there are about 300 physicians in Europe so that we have a branch called ‘Emmanuel Doctors’. Every year in the month of March, we organize a meeting of several days in Paray-le-Monial in France, the place where Jesus revealed his Sacred Heart to sister Marguerite Maria Alacoque in the 17th century and where the Emmanuel Community has its international gatherings every summer, welcoming over 30,000 people every summer, many of them rediscovering the love of God or deepening their faith. During the international meeting for physicians in March, for the tenth time next year, doctors are invited to reflect on their spiritual life and how they can apply what they learn in the medical practice.

Reason

When faith and spirituality are out first priority in ‘resisting’ the secular culture that sees death as a solution for physical and psychiatric problems – or just aging! – reason follows immediately (13). Let us reason for a moment about the root of the problem that has led to the legalization of euthanasia (14). We will do that by going back in time and acknowledging that the legalization of euthanasia in the beginning of this millennium followed upon the legalization of abortion in the early seventies, and the widespread acceptance of contraception after the introduction of ‘the pill’ in the early sixties of the 20th century – and the rejection of blessed pope Paul VI’s encyclical ‘Humanae Vitae’, 1968. Contraception is the hidden but intentional introduction of ‘death’ in human existence, in the intimate relationship between a man and a woman to be more specific, where husband and wife are more than ever ‘imaging’ God as a creative, life-giving community of love (the Holy Trinity). ‘Sterilizing’ the marital act either prevents conception or aborts life in its earliest stages. From that moment on, the door is open to abortion in later stages of still embryonic human life. And as we get to the practice, under certain circumstances, of terminating human life in the womb, it is just a matter of time before euthanasia becomes acceptable. The value of human life (Thou shalt not kill) is no longer an absolute, as, for example, the Belgian Brothers of Charity have stated in their recent ‘vision text’ on euthanasia for psychiatric patients. The antidote that I am proposing to you today, to this way of reasoning, is Saint John Paul II’s Theology of the Body (15), that offers not only a beautiful, biblically, theological reflection on human sexuality and fertility, but also an ‘adequate anthropology’ in which he reconciles a personalistic and, at the same time, Thomistic perspective – according to ‘natural law’ – on the human person. This important catechesis allows us to understand why life, in every stage, including its last stages, should be respected. Another – still somewhat debated – study that I would like to suggest is the research that has been done on the so-called ‘near-death experiences’, where, on the basis of numerous interviews with people of all beliefs, cultures and walks of life that report these kinds of experiences, the existence of life after death can no longer be reasonably denied. Among the many reoccurring experiences is the fact that many of those who ‘come back’ strongly discourage suicide and euthanasia. The absence, most of the time, of the ‘after-life argument’ in euthanasia debates seems both from a scientific as well as a religious perspective hardly justifiable. But whatever your study may be: the ‘resistance movement’ that I propose is one that includes the following three elements (16):

knowing the Catholic faith, understanding its inner logic

understanding the relationship between science and faith

understanding the moral teaching of the Church, grasping its reasonability.

Practice

The third and last field in which we may be able to resist the secular culture that tends to see death as an option is our ‘practice’ in (again) three fields (17): in medicine, in civil society and within the Church (18). As a doctor, it seems to me that you are called, first and foremost to professional excellence. But this is not enough. Your willingness and ability to witness from your religious and reasoned conviction is crucial for a change in culture. In the end, it may seem impossible but Jesus Christ himself urges us in this direction: personal holiness , or at least searching it, is absolutely necessary. Whatever can be brought against us will be brought against us: lack of kindness, patience, professionalism, negligence; anger, lack of forgiveness, being harsh on your colleague, you name it. It has always been personal holiness, that has convinced people of the truth, goodness and beauty of the Catholic faith. This means, amongst many other aspects, that our witness is always in love and in truth in the right balance of the two (19), always making the distinction between the person and his conviction and practices, as I said before. We are also not in the business of ‘convincing’ but ‘witnessing’, because getting convinced of something depends on the God given free will of the person: we cannot decide for someone else what to believe or do; we have to respect his freedom, as God does. It is also rather easy to ‘be right’, by studying the matter, good reasoning, scientific knowledge and more. But ‘being proved right’, getting the other person (colleague, politician, journalist,…) to admit that you are right, especially in ethical or religious matters, that is a far bigger challenge. It is possible is our witness passes the test of being convincing, but it is the other party who is there to judge. So we can only do our very best, in every aspect, as if our life depends on it – an in a certain sense, it does!

In order to come across better, any defensiveness or aggression is to be avoided (20). It will only harden the hearts of the other party. That does not mean that we can never be firm. But we always have to adjust the tone of our speaking and the non-verbal ways of communication to what is acceptable for the other person, in order not to lose his attention and respect for our views. Being joyful and kind is an absolute prerequisite for a more convincing witness of our beliefs and let us be patient like God is patient with us, with humanity in general. Not passive, but accepting that things can take time, whether it is in a personal relationship or in your organization, in civil society and also within the Church. Being a witness, especially here in Rome during the first three centuries of Christianity, meant accepting martyrdom to a certain degree. The very word martyr stems from the Greek word μάρτυς, mártys, meaning “witness”, as you all know very well. (So we are not talking about ‘martyrdom’ in the Islamic sense of the word!). We may not have looked a hungry lion in the face yet, but we have heard the testimonies of those who have been fired because of moral convictions, not being able to practice their profession due to the modern ‘dictatorship of relativism’ as Benedict XVI called it, the intolerance that we oftentimes experience in our so-called ‘tolerant society’, that appears to very intolerant towards people with ‘politically incorrect’ views. We can be frustrated, angry, but in the end, this will not help us to ‘resist’ or, even better, change the culture. So let us get over it and ‘love our enemies’ and pray for them.

What I am talking about, is basically an attitude of the heart (21). And for those who know about my spiritual background of the sanctuary of Paray-le-Monial, they will understand that I am talking about the attitude of the heart of Jesus, who says that he is ‘meek and humble of heart’. If we are willing to learn from Him we will find rest for ourselves (Mt 11:29). In the end, the ‘resistance movement’ that we promote is one of love, goodness and … humility, and not of anger, aggression and a fight. Once, Jesus overthrew the tables in the temple, the sacred place, the house of His father. And He could be tough with the Pharisees who totally misrepresented the Jewish faith, not even living up to it themselves. But in the end, he said to Peter to do away his sword and avoid mere human reasoning, even calling him Satan. He know that in the end, God’s love and life would conquer the culture of death.

More

At the end of this talk on the creation of a ‘resistance movement’ against euthanasia and all that has led and is still leading to its legalization, I would like to summarize my ‘prescription’ for this movement in four words: adoration, compassion, evangelization and holiness (22). And I also would like to change the title of the conference slightly, hoping that the organizers of this beautiful conference will forgive me: instead of saying that ‘Catholic health professionals can still deliver’ (23), I would like to challenge you by saying that ‘Catholic health professionals can deliver more’ (24), or at least are called to deliver more: more love, more truth and more respect for life.

Thank you very much!

Vincent Kemme holds a master in science from Utrecht University (the Netherlands) and specialized in the relationship between biology and faith, both philosophically as ethically. After a career in secondary education in the Netherlands and Belgium, he founded Biofides, an association for biology and faith. He was invited to joint the the Board of the Belgian Catholic Medical Association and is editor in chief of it’s trilingual quarterly ‘Acta Medica Catholica’. He is also member of the Bioethics Committee of the World Federation of Catholic Medical Associations. With his wife Ine, occupational therapist in Belgium, he is responsible for the Emmanuel Community in Flanders, the Dutch speaking part of Belgium. The have six children and one grandchild.