Persona humana at Fifty: Why the Church’s sexual ethics still matter today

In 2025, the Church must once again articulate—not dilute—the anthropological and moral vision that makes sense of its teaching.

December 21, 2025 John M. Grondelski, Ph.D. Essay, Features, History 62Print

December 29th will mark the fiftieth anniversary of Persona humana, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith’s (CDF) “Declaration on Certain Questions Concerning Sexual Ethics.” Issued in 1975, the document reaffirmed Catholic teaching on the immorality of three practices—fornication, homosexual behavior, and masturbation—precisely at the moment when many theologians were already seeking to dismantle the whole of the Church’s sexual ethic.

Half a century later, it will be telling to see whether this anniversary is noted, even while its message is no less urgent now than it was in 1975.

It is worth revisiting why Persona humana arose, what it taught, and what has happened since.

The Context: Aftermath of the birth control commission

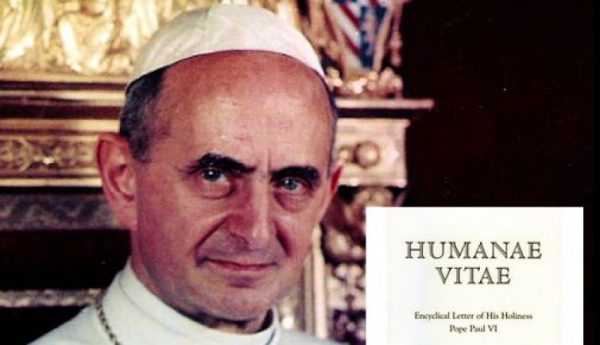

Persona humana appeared seven years after Humanae vitae. Its background lies in the progressive erosion of Catholic sexual ethics begun during the 1960s and early 1970s, a process accelerated by the famous papal birth control commission convoked under John XXIII.

The commission’s original mandate was narrow: determine whether the new anovulant drug—the “Pill”—constituted “contraception” as the Church had always understood that term. To us, that seems obvious, but it was not in 1963. Back then, contraception meant barriers that prevented gametes from meeting or chemicals that killed them. The Pill’s mechanism was different, almost unique. Its intended effect was to prevent ovulation altogether. By altering hormonal levels, the “Pill” tricked the body. Was suppressing ovulation—a preemptive action rather than an interference with a process already begun—the same kind of “contraceptive” act the Church had condemned? (I am unsure what awareness then existed of the Pill’s abortifacient nature.)

That was the question. In one sense, it was a technical question, but one that did not involve reconsidering whether contraception itself could be moral. In the early 1960s, even writers who supported contraception—including John Noonan, author of Contraception, a history of the subject—conceded that Christian witness against contraception was unanimous until 1930 (when the Anglican Lambeth Conference accepted it) and had remained unanimous in Catholicism up until that moment.

But the commission was quickly overtaken by theologians with broader ambitions. After John XXIII’s death, Paul VI continued the commission—an imprudent decision, in retrospect. The direction in which the commission’s theologians were heading was clear: allowing contraceptive intercourse. When their confidential report was submitted to the Pope in 1966, it was promptly leaked to the National Catholic Reporter.

There were two reports:

- A majority argued that the Church should change its teaching.

- A minority insisted that such a change was impossible, in part because doing so would undermine the entire structure of Catholic sexual ethics—including its teachings on masturbation and homosexual acts.

Two more years of papal indecision followed until Paul VI finally issued Humanae vitae (1968). In that document, the Pope reaffirmed the principle that grounds all Catholic sexual morality: the divinely established, inseparable connection between the unitive and procreative meanings of the marital act (#12). Human beings, he wrote, “may not break” what God Himself joined.

Because of the two-year delay, the encyclical immediately encountered organized opposition. In the United States, Fr. Charles Curran led the resistance. But it took until the late 1980s for CDF prefect Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger to declare that Curran could not present himself as a Catholic theologian.

Between 1968 and 1975, dissenters expanded their rejection of Humanae vitae from promotion of “the Pill” into a broader assault on Catholic sexual ethics. Masturbation was dismissed as developmentally insignificant, and fornication became a lifestyle choice for the era’s “authenticity.” And although homosexual acts remained largely unmentionable, figures like Jesuit John J. McNeill were already pushing for results in the direction embraced by today’s theological revisionists (McNeill was expelled from the Society of Jesus, at the request of the Vatican, in 1987).

By 1975, the CDF saw the need for a clear restatement of Catholic doctrine on these three increasingly contested practices. Persona humana was the result.

What did Persona humana teach?

Persona humana at Fifty: Why the Church’s sexual ethics still matter today – Catholic World Report