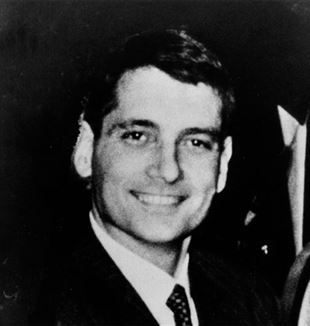

His surgical procedure has saved many worldwide, but the young doctor wasn’t just known for his contributions to the medical world. Here’s how the Rastelli exhibit at the 2018 Rimini Meeting came about.Anna Leonardi9.27.2018“Roll up your sleeves and come, boy. There is bread and glory for all.” The handwriting crowding the back of a postcard from March 1968 reveals a glimpse of the tension the young Italian cardiac surgeon Giancarlo Rastelli was experiencing on his American adventure. Nothing in those lines sent to an old friend in Italy, however, would induce suspicions of his illness: an aggressive lymphoma that would eventually lead to his death in 1970 at only 36 years old.

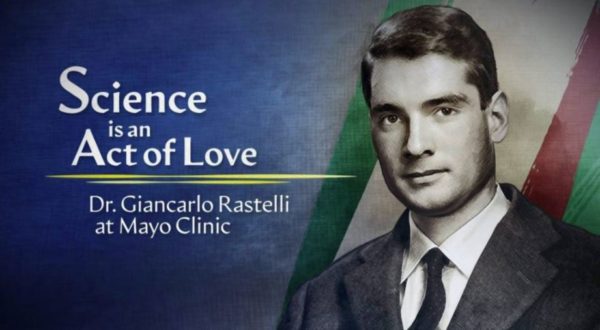

Today, his name is still well known thanks to the Rastelli procedure, an operation used to correct congenital heart defects that is still present in manuals of pediatric cardiac surgery and widely practiced in many hospitals. To discover his human depth, however, four medical students from Bologna researched and compiled an exhibit in 2017, which was then presented at this year’s Rimini Meeting in the Health area. With videos, pictures, and manuscripts, this exhibit painted a whole picture of the man’s gaze and the profound unity of knowledge and love in his life. It comes with no surprise, then, that even the United States expressed interest in it: The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, the same world-renowned hospital that welcomed Rastelli with a scholarship in 1961 and held him close until the end, would like to display it in their facilities this upcoming year.

This enthusiasm migrating from Rimini to the United States finds its roots in the same curiosity that in 2016 burst into the lives of Giovanni, Gerardo, Andrea, and Veronica, medical students from Bologna, when they first heard about Rastelli in class. “Our professor mentioned that with his discovery, Rastelli saved many children’s lives and that his cause of beatification had been opened,” said Giovanni. “Something in us was set into motion and we began looking for more information.” They found a book written by Rastelli’s sister, Rosangela. “In that biography we encountered the person and the physician we all wish to become. His life was contagious.” They spoke amongst themselves and understood that it was something they needed to share. “So, driven by our fascination and against all realistic odds—considering all our classes, exams, and internships—with some friends we threw ourselves into this project to make an exhibit for our university,” said Gerardo.

Their work began with a phone call to the Gazzetta di Parma, “We are looking for someone who could put us in touch with Rastelli’s sister.” They managed to meet her through some contacts. “Then, thanks to her, we could reach out to physicians who had studied with him, people who had known him in Parma, and even his daughter Antonella, who now lives in Padova and is a doctor herself.” Through interviews, letters, and newspaper articles, the reconstruction of Rastelli’s life was advanced thanks to historical sources collected and carefully arranged by the students. “It was striking to see how, at the very mention of Rastelli’s name, everyone would open their doors to us. They were moved by the idea that, after fifty years, some young people could be interested in their friend’s life. They had pictures and anecdotes for us as if they’d been waiting for us their whole lives.” And so, even for the four students, Giancarlo Rastelli simply became “Gian.” “He became a friend. His life is like a magnifying glass through which we see what happens to us at work, at school, and at home.”

The exhibit’s panels retraced significant milestones in Rastelli’s life. From his youth at the San Rocco parish in Parma to the very last days before his death in Rochester, the experience was guided by the narration of eye witness accounts. Their tale shed light on the details and made it possible to identify oneself with a life that, in its mundaneness, was invested in a great ideal. Along these lines, Rastelli’s university friends recounted how, after a hard day of studying, Gian would stop everyone and say, “Let’s go outside and see that thing! Come on, we’ll come back later and catch up!” Or before working on anatomy, he would say, “Do you remember the St. Paul’s Hymn of Charity?” He would recite it from memory and everyone would be astonished. Or when, in his free time, he would go fishing in the Polesine where the fishermen would address him as “Mister doctor,” and where, in between fish, he would talk to them about Italian writers, history, and geography. “Three or four of them even got their diplomas. Everyone considered that the ‘Miracul del Gian’ (the miracle of Gian).”

Dr. Giancarlo Rastelli

Soon after graduating in 1957, Rastelli began working at the surgical clinic of Parma. His relationship with his patients was defined by striking charity. “He would fall ill with the sick and heal along with them,” recalled one of them. For example, Mr. Menapace had undergone an amputation of both legs. One New Year’s Eve, his wife called Dr. Rastelli to inform him that her husband had fallen into a deep state of depression and had ceased eating and drinking. He wanted to die. Without hesitation, Gian recommended an “abundant Parma dinner” and headed over to his patient with some friends. He spoke with him for over an hour. “We don’t know what they talked about, but the result was that, at a certain point, Armando Menapace called everyone in, opened a bottle of Lambrusco from his vineyard, and cut the culatello from his hogs. He cried. He laughed. He ate. And he started living again that day.” When Gian left for America, the friends that were with him that night continued visiting Mr. Menapace.

The stories of Rastelli’s years in the United States were also told by the direct witnesses of many colleagues. His charity never went unnoticed: “He had a cot he would use secretly, because it was prohibited, when he wanted to stay overnight to keep an eye on the patients in grave conditions. He didn’t feel right going home.” There were also hundreds of Italian children suffering of congenital heart disease who would cross the ocean with their families to have Rastelli operate on them. He had become the “surgeon of possibility.” He would visit them for free and he would make it so that they could embark on the costly trip to the Mayo Clinic. He hosted many of them in his own home.

Within all these activities, Rastelli’s humanity was sustained by the presence of his wife Anna. They met on the Bormio ski slopes and after their wedding in 1964, she followed him to the United States where, in the following months, they learned of Gian’s illness. The way they faced this is documented in the letters the two wrote to each other during those years, as well as their daughter Antonella’s memories, some of which she shared for the exhibit. “The night of the diagnosis, he came home with a red rose for his wife Anna. He played Vivaldi on the gramophone and he said, ‘I took some tests and they didn’t go very well. I am happy. I have had much in life and now, with you, I have had it all.’” A few days later, he said, “I was granted some more time, thank God. Let’s not talk about it anymore. Let’s live a normal life.” And it was so for six years. During that time, Rastelli published the discoveries for which he is still remembered today. Anna gave birth to Antonella in 1966. “He managed to remain himself,” recalls his sister in her biography. He died on February 2, 1970. Shortly before the agony preceding his death, he said to his wife, “Pay the price of our love. We’ll see each other again.” He then looked outside and added, “The sun is so beautiful.”

Before reaching the Rimini Meeting, the exhibit was displayed at the Bambin Gesú in Rome, at the University of Parma, and at the University of Padova. At the latter, it was an integral part of a course and a conference for physicians. The encounter with Rastelli’s human and scientific journey is contagious everywhere. Professor Gaetano Thiene, expert of congenital heart disease in Italy, for example, was contacted by the four medical students and, after having read a proposal for the exhibit, made himself available to help them with the scientific background.

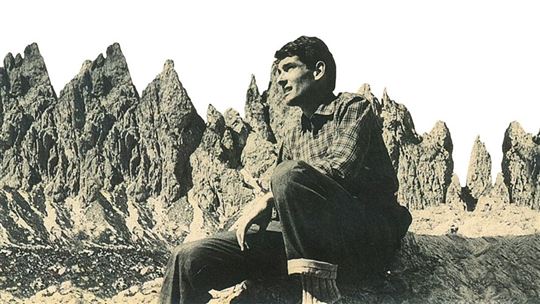

Rastelli, however, is not only for those in the medical field. The repairman of the Saint Orsola in Bologna had a very similar experience to Thiene. Early one morning, he had just finished some repairs in the exhibit hall and he decided to give the panels a quick look. Seeing the title, “The First Charity for the Patient is Science,” he assumed it was just “doctor stuff.” However, he was taken by a picture of Rastelli on top of the Dolomites, wearing a flannel shirt and hiking boots. He looked tired, probably from the hike, but his gaze was tending towards an invisible endpoint. “Did you make this stuff?” He asked the students when they showed up to lead the tours. “I’ve never read anything like this. Mind you, I’m an atheist, but I see something more here.” He bent over his tools to put them away and continued, “You know, my son needs heart surgery soon. I hope to meet someone like this Gian.” He left, but he came back shortly after, whistling to himself and waving a check in his hand. “I paid for everyone’s breakfast. Come on, go to the café. I’m happy today.”

CL