The art of fencing and painting with a half brain.

Antonio M. Battro MD, PhD (1)

Academia Nacional de Educación. Argentina

To Howard Gardner, who inspired so much my work with Nico

(Published with permission to the FIAMC)

When Nico was three years and seven months old he was submitted to a right functional hemispherectomy to stop a devastating and intractable epilepsy. This successful intervention permitted him to grow up as a charming and intelligent child in a healthy and supporting family, and he is now a young man full of projects. I met with Nico when he was five years old and started to give him support during his early schooling with the help of computer and communication technologies and with the remarkable collaboration of Lucía Maldonado (Battro, 2000). Since then I continue in contact with him and his wonderful family. Nico finished elementary school in Buenos Aires and entered high school in Madrid where he now lives. He discontinued his studies when he was eighteen but he expects to finish them later. Meanwhile he got a special certificate on informatics for secretarial work as a disabled person. And most importantly, he is thriving in his family life and in an increasing extended social environment. In particular, he has discovered two fascinating fields in which to display his talents: the arts of fencing and painting. He became an amateur fencer (foil, epée and sabre) and a member of the national team for fencing in a wheel chair. He is very conscious of this social recognition and showed me with pride the card that credits this exceptional condition. This young man now has a dream: to become a professor of wheel chair fencing. And, most remarkable, he is also becoming a sensitive painter! How could Nico, who is hemiplegic and hemianopic, and who had a profound loss of gray and white matter as a result of his right hemispherectomy, succeed in the arts of fencing and painting?

Science is friendship: Nico´s network

I will try to reflect on this exceptional case and recognize my friends, fellow scientists, and educators who supported and continue to help Nico in Argentina, United States, Spain, France and Singapore…I am convinced that “science is friendship”, even our very modest “microdiscoveries” are the result of an enormous network of people and circumstances (Battro, 2006).

I started to write about Nico at Harvard as a visiting scholar at the Graduate School of Education in 1997 and gave a first talk there in 1998 on the “education of a half brained child.” I received comments on my written work on Nico from Howard when I was visiting Singapore in 1998. His suggestions helped me to focus on the important issues of my endeavour. In Singapore I also received the generous collaboration of Ralf Kockro and Yeo Tseng Tysai of the Kent Ridge Digital Lab KRIM, who simulated Nico’s functional right hemispherectomy on a Dextroscope used in Computer Aided Surgery. Out of this came a book Half a brain is enough: The story of Nico in 2000 (Battro, 2000) which contains the virtual brain images from this collaboration. I also had the generous support of Kurt Fischer who gave me also the wonderful opportunity to discuss this book with him at an Askwith Education Forum at Harvard in 2001. During my stay at Harvard as Visiting Professor (2002-2003) I had many more opportunities to work with Nico, who visited Harvard with his parents in 2002. In particular I worked with Russ Poldrack, Jane Bernstein and Mary Helen Immordino-Yang who wrote a most remarkable doctoral dissertation on the comparison between two “mirror” hemispherectomies, right (Nico) and left (Brooke) in the realm of language, syntax, semantics and prosody, and emotions (Immordino-Yang, 2005, 2007, 2008). A new extended study by Stanislas Dehaene and his team at the Neurospin Lab in Saclay, France, will help us to better understand Nico´s astonishing motor, perception and cognitive development as revealed today in fencing and painting

Lesion and Compensatory Analysis

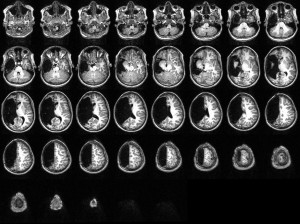

Standard neurological “lesion analysis” (Damasio and Damasio, 1989) is important to describe the behavioral and cognitive troubles associated with Nico’s loss of the right hemisphere with an intact cerebellum (Fig.1). His hemiplegia inhibits him from accurately performing with his left arm and hand. He limps but manages to walk very well and even to run and swim. His left hemianopia does not impair his good reading or writing skills, or his fencing and painting talents. A “compensatory analysis” is now needed to complement the whole picture of such a remarkable feat of neuroplasticity. This is our next challenge.

Vision with the left hemisphere

In order to move skillfully in the difficult game of defense and attack in fencing, a thorough three-dimensional vision– good stereopsis — is required. Stereopsis is considered a right-hemisphere dominant process, but surprisingly Nico has stereoscopic vision without a right visual cortex. He passes the tests of random-dots stereograms of Bela Julesz (1971) with ease. It is impossible to cheat on this test, where several colored anaglyphs of random-dots are viewed with red and green filters. Julesz notes that human, even babies, have a “cyclopean vision” that fuses the images of the two retinas in the cortex. In the case of Nico only the left visual cortex is functional. It is clear that his left hemisphere is competent enough to process all the 3D cues in the difficult art of fencing.

Another aspect concerns the higher-level visual and cognitive integration and differentiation of local details and global forms that are essential in the visual arts. A classic neuropsychological test is to present a target stimulus made out of small parts, a large letter M, composed by small letters z, for instance. Patients with a right-brain lesion detect the small components (the z) but lose the global form (the M), while patients with left- brain lesions do the opposite. What is really amazing is that in spite of his right hemispheroctomy Nico performs as a normal person correctly reproducing both local details and global forms. He is perfectly “glocal”. This ability is certainly key for an artist in drawing and painting. But we still do not know much about how this amazing compensation is taking place in his left brain. In other words, in order to advance in the practice of “neuroeducation” we have to understand the complex dynamics of human neuroplasticity (Battro, Fischer and Léna, 2008: Battro, Dehaene and Singer, 2010).

Arts and sports

Having followed Nico’s development for more than fifteen years, I can testify to how much he has improved in his motor skills. He belongs to a family with strong professional involvement with sports, who gave him the needed support. He learned to swim, play tennis, ride a bicycle, play soccer. And in the last years he became more and more involved in fencing. This was a very clever choice, fencing being mostly an exercise for one side of the body. In the case of Nico he uses his able right arm and leg.

He started several years ago in a regular class of fencing and he practiced in an upright position with companions of all ages. The first years he practiced only with foil, but now he is also fencing with epée and sabre, which require a completely different set of motor skills. Recently he was offered the opportunity to practice with motor disabled persons who were competing on wheel chair. He was forced to sit on a wheel chair to be at the same competitive level with their team of disabled sportsmen and change accordingly the body schema for fencing, a difficult motor shift indeed. He did so well that he was invited to participate in national and international fencing competitions for disabled on wheel chair. In this difficult sport both wheel chairs are fixed at a given distance and the game is centered in the quick movements of the upper part of the body and of the arm and hand. Nico has now discovered a new sport he loves so much that he would like to become a professor in the specialty of fencing on wheel chair. Moreover he is still practicing regular fencing with non-disabled companions. This allows him to take part in many social events. He is certainly very proud of it. It would be important to analyze in an experimental setting, with some wearable brain imaging equipment, the role of his left brain and his intact cerebellum to process the remarkable shifts of his body image passing from the upright to the seated position of fencing. Recently he spent a long time with me to explain the tricks and skills needed for fencing on a wheel chair. It was an amazing description, very accurate and sensible. His “intrapersonal intelligence” in this case was to the point.

The art of painting and drawing

Nico’s drawings in his early childhood were still poor when using his right and able hand. I could never imagine the unfolding of an artist from his limited “analog” of artful scribbles (Gardner, 1980). I tried to help him to draw and paint using the “digital cognitive” skills embedded in the “turtle art” developed by Seymour Papert with the LOGO computer language. He made some interesting work in this field in elementary school when he was eight years old (Fig. 2). Later, during some trips abroad we started to enjoy making drawings together and at some point Nico made a leap forward.

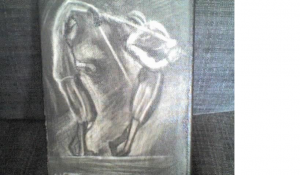

The important issue is that now as a young man Nico loves painting very much and attends art lessons in an atelier near his home. In a visit to Paris he spent a lot of time in the museums trying to recognize those classic paintings he was copying in the atelier. A beautiful copy he did of Claude Monet’s “Impression Soleil Levant” hangs on a wall at his house. He showed me also paintings of fencing inspired by photos (Fig. 3). A series of these paintings in small format became his first exhibit in the atelier. He was proud because he sold them (at a modest price) and gave one to me as a gift, when I told him that I was willing to offer it as an award to the best presentation by a young neurocognitive scientist at our annual international workshop on Mind, Brain and Education at the Ettore Majorana Foundation and Centre of Scientific Culture at Erice, in Sicily. He wrote me a very sensitive email as a donor. This year I bought another painting by him for another prize at Erice—a large still life. The fact that these paintings were done by a talented hemispherectomized artist was particularly appreciated by the winners and the participants, many of them engaged in diverse activities of neuroeducation around the world.

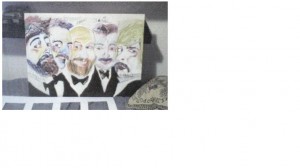

Nico now paints interesting landscapes and still life and also remarkable portraits from photos (Fig.4). But for me a most amazing achievement was a self-portrait he made using a mirror. He explained me in detail how he had proceeded in this difficult task. A half-brained-self-portrait (Fig. 5)! This complete portrait is in clear contrast with cases of left-side neglect in the self-portrait of adult artists with a right brain lesion. Compensation analysis should find an explanation for this fact. How could it be that the total removal of one hemisphere in infancy may have lesser cognitive consequences than a local adult lesion?

To sum up, Nico is thriving in the art of fencing and in the art of painting, two independent high-level cognitive, perceptual and motor skills. Most interesting he is spontaneously working to build a bridge among both activities using any opportunity to represent the art of fencing on canvas. This original kind of synthesis is a sign of Nico’s search for inner unity. A good example for all of us.

References

(1) In: Kornhaber, M., & Winner, E. (Eds.). (2014). Mind, Work, and Life: A Festschrift on the Occasion of Howard Gardner’s 70th Birthday, with responses by Howard Gardner (Vols. 1-2). Amazon via CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

http://howardgardner01.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/festschrift-_-volumes-1-2-_-final.pdf.

Battro, A. M. (2000). Half a brain is enough: The story of Nico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Battro, A. M. (2006). Microdiscoveries: A fractal story. Case study of creative paths and networks in science. Paths of discovery. Pontifical Academy of Sciences: The Vatican

Battro, A. M., Fischer, K. W. & Léna, P. J (Eds). (2008) The educated brain. Essays in neuroeducation. Cambridge University Press.

Battro, A. M., Dehaene, S. and Singer, W. J. (Eds). (2010). Human neuroplasticity and education. Pontifical Academy of Sciences: The Vatican.

Damasio, A. and Damasio, H. (1989). Lesion analysis in neuropsychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gardner, H. (1998). Artful scribbles: The significance of children´s drawings. New York; Basic Books.

Immordino-Yang, M. H. (2005). A tale of two cases: Emotion and affective prosody after left and right hemispherectomy. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Harvard University Graduate School of Education.

Immordino-Yang, M. H. (2007). A tale of two cases. Lessons for education from the study of two boys living with half their brains. Mind, Brain and Education, 1, 66-83.

Immordino-Yang, M. H. (2008). The stories of Nico and Brooke revisited: Towards a cross-disciplinary dialogue about teaching and learning. Mind, Brain and Education, 2, 49-51.

Julesz, B. (1971). Foundations of cyclopean vision. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Figures

Fig 1. Images of Nico’s functional right hemispherectomy (courtesy of Russ Poldrack)

Fig.2. Turtle LOGO art (Nico at age eight)

Fig. 3. The art of fencing: A painting inspired by a photo.

Fig. 4. Portraits

Fig. 5. Self-portrait